ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Oral cleft is the second major cause of congenital anomalies and represents a major craniofacial alteration in live births. The objective of this study was to analyze the epidemiological data collected from the Center for Comprehensive Care to Individuals with Cleft Lip and Palate in the period from January 2011 to December 2014.

METHODS: This retrospective study evaluated 1,262 medical records of patients with an oral cleft. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 52.7% of the medical records were included in the study.

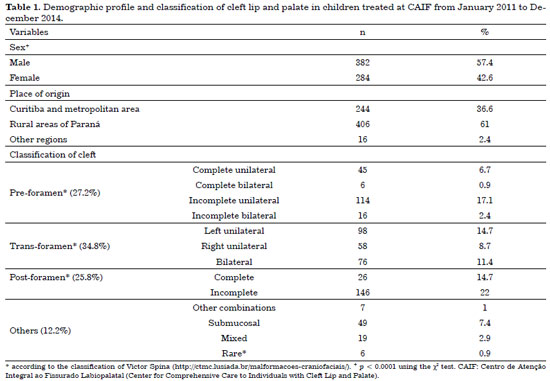

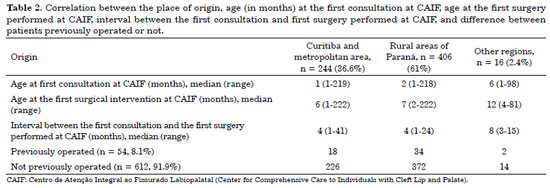

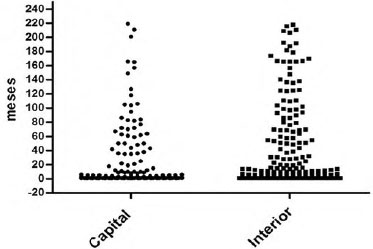

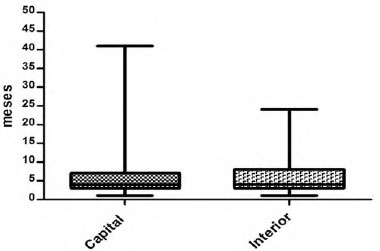

RESULTS: Among the 666 medical records, 57.4% were of male patients and 42.6% were of female patients. Of these, 34.8% of the patients had a trans-foramen cleft, 27.2% had a pre-foramen cleft, 25.8% had a post-foramen cleft, and 12.2% had another type of cleft. Patients from Curitiba and the metropolitan region constituted 36.6% of the cases, and patients from rural areas of Paraná represented 61% of the visits to the care center. The median age at the first visit of the patients from Curitiba/metropolitan region and rural areas of Paraná was 1 and 2 months, respectively. The first surgery was performed at the care center at the age of 6 months in patients from Curitiba and metropolitan region and 7 months in patients from rural areas of Paraná.

CONCLUSION: There was a predominance of boys and a higher prevalence of incomplete post-foramen clefts in the total population. Despite the long distance to the care center, children from rural areas of Paraná underwent the correction surgery and were treated at the referral center with an age difference of only 1 month compared with patients who lived in Curitiba, where the care center is located.

Keywords:

Epidemiology; Cleft lip; Reconstructive surgery.

RESUMO

INTRODUÇÃO: A fissura oral é a segunda maior causa de anomalias congênitas e representa a principal alteração craniofacial em nascidos vivos. O objetivo do presente estudo foi determinar os dados epidemiológicos do Centro de Atenção Integral ao Fissurado Labiopalatal, no período entre janeiro de 2011 e dezembro de 2014.

MÉTODOS: Estudo retrospectivo utilizando prontuários clínicos. Foram avaliados 1262 prontuários de pacientes portadores de fissura oral. Após aplicação dos critérios de inclusão e exclusão, 52,7% prontuários foram incluídos no estudo.

RESULTADOS: Entre os 666 prontuários, 57,4% foram do gênero masculino e 42,6% do feminino. Verificou-se que 34,8% dos pacientes apresentaram fissuras transforame, 27,2% fissuras pré-forame, 25,8% fissuras pós-forame e 12,2% outros tipos de fissuras. Pacientes oriundos de Curitiba e Região Metropolitana correspondem a 36,6%, aqueles do Interior do Paraná abrangem 61% dos atendimentos no Centro de Atenção. As medianas de idade na primeira consulta, entre os pacientes de Curitiba e Região Metropolitana e do Interior do Paraná, são de 1 mês e 2 meses, respectivamente. E a primeira cirurgia, realizada no Centro de Atenção, foi em torno de 6 meses, nos pacientes de Curitiba e Região Metropolitana, e de 7 meses naqueles oriundos do Interior do Paraná.

CONCLUSÃO: Verificou-se predomínio de fissuras em meninos e maior frequência da fissura pós-forame incompleta. Observou-se que, apesar da distância, as crianças oriundas do Interior do Paraná realizaram a cirurgia de correção e chegaram ao centro de referência com apenas um mês de diferença em relação aquelas da cidade sede do Centro de Atenção Integral ao Fissurado Labiopalatal.

Palavras-chave:

Epidemiologia; Fenda labial; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos.