INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death in women and the most incident

globally, with a rate of 2.1 million new cases in 2018 and a percentage of 6.6%

of total deaths from all types of diseases1. Considering the Brazilian incidence, after non-melanoma

skin tumors, breast cancer is also the most common among women and the leading

cause of death from cancer in the population, representing 16.5% of all deaths

in 2014- 20202. In addition,

66,280 new cases were estimated for 2020, indicating an incidence of 43.74 cases

per 100,000 women3.

Mastectomy, which removes one or two breasts through a surgical procedure, is

performed when other treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are not

effective, either because of the advanced stage of the tumor or its location. It

is a milestone for women who need to undergo it due to the consequences in these

women’s lives4,

affecting their femininity and self-image, as the breast symbolizes the feminine

sphere. These impacts affect the patient’s entire social life, from

romantic relationships to professionals, as many women become ashamed of their

own bodies. The surgery impacts not only aesthetic and physical, but also

emotional, self-esteem, and sex life4.

Due to the large recurrence of late breast cancer diagnosis and the delay in

accessing appointments, exams, biopsy and treatment, approximately 70% of

diagnosed patients will need to have their breast removed5. According to Law 11,664/2008,

the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS - Sistema Único de

Saúde - in portuguese) should ensure that all women, from 40

years of age, undergo mammography as a way of preventing and detecting neoplasia

in its initial form since the incidence and mortality of this pathology tends to

grow progressively in this age group6. However, it is observed that such examination is performed

in the SUS, only in ages between 50 and 69, under the guidance of the Ministry

of Health7. It is important to

note that under the age of 40, there are fewer than 10 deaths per 100,000 women,

while in the age group over 60 years, the risk is 10 times greater, thus showing

the importance of early diagnosis3.

With the progression of cancer or even cancer treatment, some women may suffer

some mutilations in the breast. As a way of restoring the esthetic standard,

they are assured of immediate reconstructive plastic surgery8. The purpose of reconstructive

plastic surgery is to reestablish the region’s regular anatomy and

restore the self-esteem lost by some women during surgical treatment9. However, some problems can be

observed in this process, such as cases of breast seroma, hematomas, necrosis,

dehiscence, asymmetry and late venous thrombosis, which in some cases can lead

to the patient’s death10. Other problems are intrinsically related to SUS support

for patients, such as the lack of trained doctors and the structure to carry out

the necessary procedures11.

SUS neglected the right to surgery reparatory until 1999 when it became their

right. Despite this achievement, it was only in 2013 that the surgery had a

deadline to be performed, which should occur soon after the mastectomy or as

soon as the woman presents conditions for it8. Furthermore, in 2018, the right to surgery on both

breasts was approved to ensure symmetry10. Thus, this article seeks to answer the major impacts

caused by mastectomy in women in Brazil. Therefore, the study’s objective

was to highlight the importance of performing plastic surgery for women with

mastectomies and to elucidate the rights of these patients guaranteed by SUS in

Brazil during the process.

METHODS

This study has a qualitative approach, with a descriptive and exploratory

purpose, having used the bibliographic review of the integrative type as a data

collection technique.

The Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), PubMed and Latin American and

Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) platforms were used for data

collection. Google Scholar platform was used for further research. The search

was performed using the Boolean descriptors and operators: “plastic

surgery” OR “reconstructive surgery” AND

“neoplasm” OR “breast carcinoma in situ” OR

“unilateral breast cancer” OR “mastectomy” AND

“unique health system” OR “legislation.” In

addition, the resolutions of the Legislation Portal (http://www4.planalto.gov.br/legislacao/)x addressed

women’s rights concerning breast reconstruction surgery in the SUS were

consulted.

As exclusion criteria, articles before 2010 that addressed non-mammary neoplasms,

dissertations on surgical techniques and the diagnosis of tumors, as well as

studies carried out in patients in countries other than Brazil, were

disregarded. Studies that described the benefits reported by patients, or by the

literature itself, of performing post-mastectomy breast reconstruction, in

addition to articles that addressed the role of the SUS in reconstructive

surgery in terms of management and epidemiology. There was no language

restriction.

The results of the articles were evaluated through thematic content analysis. The

themes most discussed by the patients were counted when reporting their

perception during the mastectomy process and after reconstructive surgery. This

type of analysis allows for quantifying the frequency of the most discussed

topics, whose results were processed using Excel 2010 software.

RESULTS

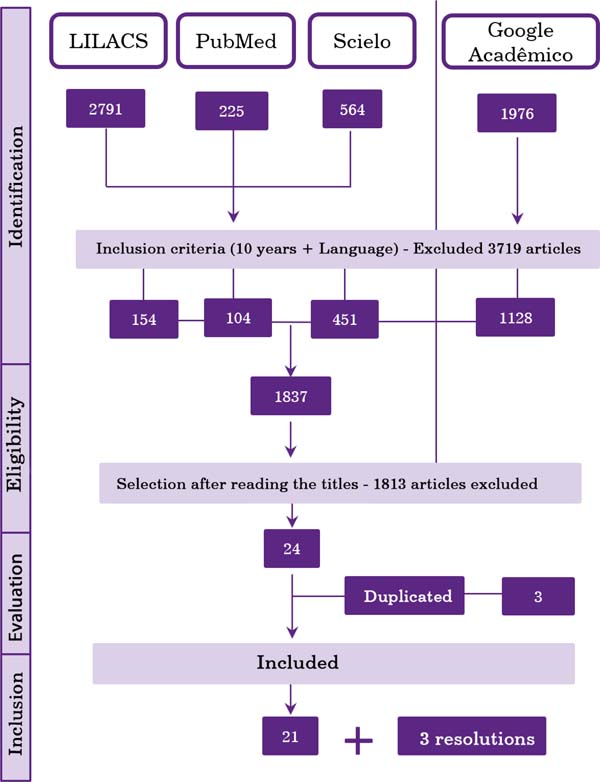

Five thousand five hundred fifty-six articles were found. After applying the

filters (articles with full text on the platform, published in the last ten

years) and an initial reading of the titles and abstracts, it resulted in 21

studies discussing the results. In addition, three resolutions were included,

found on the Legislation Portal, as shown in Figure 1.

Of the selected articles, 16 addressed mainly the relationship between the

performance of breast reconstructive surgery and the improvement of the

woman’s quality of life, 2 about the feeling of post-mastectomy women, 1

addressed the comparison of the emotions of women who underwent or not breast

reconstruction, and 2 discussed the role of SUS and public health about cosmetic

surgery. In addition, the years of publication with the most selected studies

were 2013, 2017 and 2019, with 4, 3 and 4 works, respectively. However, two

articles from 2010, 2012, 2016 and 2020 were still selected; and one from 2015

and 2018, as shown in Chart 1.

From the resolutions found on women’s rights regarding breast

reconstruction after mastectomy performed by SUS, Laws n° 9797, n°

12802 and n° 13.770 were selected, published respectively on May 6, 1999,

April 24, 2013, and December 19, 2018.

Profile of women with mastectomies

The analysis of 19 articles about women with mastectomies showed that, in

general, they have a profile between 41 and 60 years of age. In addition,

most articles show a predominance of white participants with complete

elementary education and Catholics (Chart 2).

Relationship between performing reconstructive surgery and the

woman’s perception of her body

Among the 16 studies analyzed, which mostly addressed the relationship

between performing breast repair surgery and improving the quality of life

of women, 42.1% said that women felt anxiety, followed by feelings such as

fear, depression and sadness (Table 1). In addition, some of the patients had decreased sexual desire,

avoiding any intimate contact.

Among the included studies, an analysis of satisfaction with the breast,

psychological and sexual well-being was presented by comparing 79 patients

who underwent augmentation mammoplasty and 64 who did not. Of these, it was

observed that patients undergoing reconstruction improved their self-image

and feeling of overcoming cancer12. In addition, comparing before and after the

reconstruction surgery, an increase in the patients’ physical and

mental well-being was observed13. Therefore, it is generally possible to see that

patients’ quality of life after breast reconstruction with breast

implants is superior concerning the period before the procedure.

In the study by Carneiro et al. (2020)14, the assessment of these women’s feelings

was also quite significant, with feelings of fear, shame, suffering,

depression, loss, dissatisfaction being reported before the aesthetic

procedure, which seem to decrease, or even disappear, after the surgery, as

you can see in the patients’ statements:

“[...] I was very satisfied with the plastic surgery for breast

reconstruction, it was as if I had been reborn, it’s another

condition of life! I came back to life!” (p. 47746)

“[...] Knowing Ora of joy, right! Because I imagined that I would have

that defect there, that we would look at, and see that thing without...

right! Small right, but it is always defective, right. There was that

emptiness, ugly thing there that I needed to do, so I resigned myself, but

always nervous. It’s a lot of suffering. After the surgery to redo

the breast, I dared to leave.” (p. 47746)

Chart 3 presents the main feelings

brought by the articles of the patients after reconstructive surgery. In

general, surgery is an option to reduce the negative emotions that are

caused by the disease and the treatment, to improve self-esteem by replacing

the “empty space” with a breast, facilitating clothing and

seeing oneself body, changing the feeling of mutilation to a sense of

renewed femininity and sensuality10. When comparing factors such as the age of the

patients, it is possible to highlight that in physical aspects, younger

women had better results, which indicates that it is associated with a lower

presence of comorbidities in this age group, as well as in mental aspects,

young women demonstrate a greater impact on self-esteem, which is expressed

by the greater attachment to the body and following the standards of beauty

imposed by society4.

The role of the SUS in the quality of life of women with

mastectomies

According to Law No. 9,797, it was decreed as mandatory to carry out breast

reconstructive plastic surgery by the network of units part of the SUS in

mutilation cases after cancer treatment15. Some changes arose in Article 2nd when

a new law was enacted, Law No. 12,802, adding two paragraphs. The

1st is to ensure that the reconstruction will be carried out

when technical conditions exist at the same surgical time. The

2nd addresses the case impossibility of immediate

reconstruction. The patient has the right to be referred for follow-up and

will be guaranteed to undergo surgery immediately after reaching the

necessary clinical conditions8.

Figure 1 - Flowchart of article collection in Latin American and Caribbean

Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), PubMed and Scientific

Electronic Library Online (SciELO) platforms. Using Google Scholar

as a complementary source. The arrows indicate the selection of

articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria set out

in the methodology.

Figure 1 - Flowchart of article collection in Latin American and Caribbean

Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), PubMed and Scientific

Electronic Library Online (SciELO) platforms. Using Google Scholar

as a complementary source. The arrows indicate the selection of

articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria set out

in the methodology.

Chart 1 - Data from selected articles for the study.

| Author |

Date |

Title |

Magazine |

Type |

Subject |

| Loyal et al.12 |

2010 |

The body,

cosmetic surgery and collective health: a case study.

|

Journal of

Science and Public Health

|

Case

study

|

Relationship of cosmetic surgery with collective health and

health promotion.

|

| Moura et al.13 |

2010 |

The feelings of post-mastectomized

women.

|

Anna Nery School of Nursing Magazine |

Descriptive Qualitative Study |

How women feel after mastectomy. |

| Cesnik and Santos14 |

2012 |

Mastectomy

and sexuality: an integrative review.

|

Psychology

Journal: Reflection and Criticism

|

Integrative

review

|

Impact of

cancer and mastectomy on women's sexuality.

|

| Majewski et al.15 |

2012 |

Quality of life in women who underwent

mastectomy compared to those who underwent conservative

surgery: a literature review.

|

Journal of Science and Public Health |

Literature review |

Comparison between women who underwent a

mastectomy and those who underwent conservative

treatment.

|

| Cosac et al.16 |

2013 |

Breast

reconstructions: a 10-year retrospective study.

|

Revista

Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica

|

Case

study

|

Analysis of

post-mastectomy breast reconstruction cases for breast

cancer.

|

| Colombo17 |

2013 |

Assessment of the degree of satisfaction of

patients undergoing breast reconstruction.

|

Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia

Plástica |

Retrospective study |

Patient satisfaction after breast

reconstruction.

|

| Furlan et al.4 |

2013 |

Quality of

life and self-esteem of mastectomized patients undergoing or

not breast reconstruction.

|

Revista

Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica

|

exploratory

qualitative study

|

Quality of

life of mastectomized patients undergoing or not breast

reconstruction.

|

| Gomes and Silva18 |

2013 |

Self-esteem assessment of women undergoing

breast cancer surgery.

|

Text and Context Nursing |

Cross-sectional observational study |

Self-esteem of women after cancer

surgery.

|

| Guimarães et al.19 |

2015 |

Sexuality

after augmentation mammoplasty.

|

Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia

Plástica |

Case

study

|

Assess

sexuality after augmentation mammoplasty.

|

| Braga et al.9 |

2016 |

Breast reconstruction process in

mastectomized women.

|

Interdisciplinary Magazine |

Literature review |

Process involved from mastectomy to breast

reconstruction.

|

| Thais Rodrigues Guedes20 |

2016 |

Body image

of women undergoing treatment for breast cancer.

|

|

Masters

dissertation

|

Self-esteem

of cancer patients

|

| Alves, VL et al.21 |

2017 |

Early assessment of the quality of life and

self-esteem of mastectomized patients undergoing or not

breast reconstruction.

|

Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia

Plástica |

Cross-sectional, comparative and analytical

observational study

|

Make a comparison about the self-esteem of

mastectomized patients undergoing reconstruction and those

who did not undergo plastic surgery.

|

| Martins, et al.22 |

2017 |

Immediate

breast reconstruction versus no post-mastectomy

reconstruction: a study on quality of life, pain and

functionality.

|

Physiotherapy and Research Journal |

Cross-sectional descriptive study |

Comparison

between immediate breast reconstruction versus no

post-mastectomy reconstruction.

|

| Villar et al.23 |

2017 |

Quality of life and anxiety in women with

breast cancer before and after treatment.

|

Latin American Journal of Nursing |

Prospective observational study |

Before x after women being treated for breast

cancer.

|

| Casassola et al.24 |

2018 |

Satisfaction with breast cancer surgery: Comparison between

mastectomized patients with and without breast

reconstruction.

|

International Exhibition of Teaching, Research and

Extension

|

Qualitative

study

|

Comparison

between women with mastectomies who underwent plastic

surgery and those who did not.

|

| Archangel et al.25 |

2019 |

Sexuality, depression and body image after

breast reconstruction.

|

Clinics |

Case study |

Quality of life after breast

reconstruction.

|

| Cammarota et al.10 |

2019 |

Quality of

life and aesthetic result after mastectomy and breast

reconstruction.

|

Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia

Plástica |

Case

study

|

Quality of

life of women undergoing breast reconstruction after cancer

treatment.

|

| Cosac et al.26 |

2019 |

Breast reconstructions: a 16-year

retrospective study.

|

Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia

Plástica |

Case study |

Analysis of post-mastectomy breast

reconstruction cases for breast cancer.

|

| Volkmer et al.27 |

2019 |

Breast

reconstruction from the perspective of women undergoing

mastectomy: a meta-ethnography.

|

Text and

Context Nursing

|

Literature

review

|

What do

women undergoing mastectomy think about breast

reconstruction?

|

| Carneiro et al.28 |

2020 |

Psychological repercussions of plastic

surgery in mastectomized women.

|

Brazilian Journal of Development |

Literature review |

Quality of life of women who underwent

mastectomies after plastic surgery.

|

| Mollinar et al.11 |

2020 |

Oncoplastic

and reconstructive surgery of the breast: analysis of the

patient's rights within the scope of the SUS.

|

Brazilian

Journal of Development

|

Literature

review

|

Rights of

SUS patients for mastectomy and breast reconstruction.

|

Chart 1 - Data from selected articles for the study.

On December 19, 2018, Law No. 13.770 was created, in which three paragraphs

were added to Article 1st, with the 1st paragraph to

ensure that the breast reconstruction will be carried out during the

surgical time of the mutilation when technical conditions exist, the

paragraph 2nd in the event of the impossibility of immediate

reconstruction, the patient will be referred for follow-up and will have the

right to undergo surgery immediately after having the necessary clinical

conditions, and paragraph 3rd guarantees that the procedures will

symmetrize the contralateral breast and reconstruct the nipple-areola

complex integrate reconstructive plastic surgery16.

DISCUSSION

The age group in the literature for mastectomized patients was a little lower

than the Ministry of Health recommended starting performing breast cancer

screening (50 to 69 years). It is possibly due to excessive exam requests

resulting in unnecessary treatments and earlier exposure to ionizing radiation

in women, implying more risks than benefits with advancing age17.

The most prevalent age can be explained by the epidemiology of the disease, being

more common in women at the end of their childbearing lives. Menopause is the

main risk factor for the disease, even more determinant than lifestyle habits

and genetics11. As for family

income, it is common for screening and the search for the health system to

happen early in women who are part of a socioeconomic population with higher

income, as this population has easier access to the private health system,

health insurance, as well as greater access to information about the pathology

and its clinical course18. In

addition to the lower search for disease tracking, women with lower income, less

education, and housewives are more likely to affect mental health, developing

pathologies such as anxiety and eating disorders, making them even more prone to

worse psychic progression after mastectomy.19

Breast cancer has a high prevalence and causes a great impact on women’s

lives, affecting both their physical and psychological aspects20. Since the diagnosis is

confirmed, the female identity starts to be questioned by the patient; after

all, the breasts are considered a symbol of femininity and body beauty21. Therefore, breast

reconstruction surgery has caused great satisfaction in post-mastectomized

patients, as it is a good alternative to improve their self-esteem.

Chart 2 - Epidemiological profile of women who underwent mastectomy according

to the chosen articles.

| Variables |

Observed

profile

|

| Age

group

|

More than 60%

of women aged 41-60 years.

|

| Color |

It depends on the study's region, but it has a

greater predominance in white women.

|

| Education |

More than 60%

of women have education (in years) from 1 to 9 years,

corresponding to complete primary education.

|

| Family income |

Family income is around 1 to 3 minimum

wages.

|

| Religion |

It follows the

regional pattern, tending to follow the national average, with

more than half Catholic.

|

Chart 2 - Epidemiological profile of women who underwent mastectomy according

to the chosen articles.

Table 1 - Feeling about mastectomy. The percentage corresponds to the number of

articles that cited each feeling concerning the total of 16.

| Feelings |

% of

articles

|

| Anxiety |

42.1 |

| Fear |

31.5 |

| Depression |

21.0 |

| Sadness |

15.7 |

| Fault |

10.5 |

| Anguish |

10.5 |

| Insecurity |

10.5 |

| Conformism |

5.2 |

| Defensive posture |

5.2 |

| Shame |

5.2 |

| Worry |

5.2 |

| Inferiority |

5.2 |

| Feeling of worthlessness |

5.2 |

Table 1 - Feeling about mastectomy. The percentage corresponds to the number of

articles that cited each feeling concerning the total of 16.

Thus, mastectomy can cause emotional and psychological distress, with significant

improvements after breast reconstruction22. Still, it is important to emphasize that women have a

higher rate of depression than men, which may highlight some biopsychosocial

factors, such as educational and historical issues, and face losses as possible

explanations for this indicator23.

The changes suffered in the body generate difficulty for women undergoing

treatment for breast cancer, mainly due to prejudice and stigma associated with

this disease21. This is

related to the side effects of the treatment, the main ones being menopause and

alteration in the production of sex hormones9. These hormonal changes can also cause problems such as

vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, even vaginal atrophy, which brings another

psychological shock to the woman, making healthy sexual intercourse a

challenge24.

Chart 3 - Main factors observed in the change in the quality of life after

breast reconstruction after analyzing the articles by Monteiro et al.

(2015)x, Furlan et al. (2013)4, Ng et al. (2016)12 and Zhong et al.

(2013)13.

| Main

changes after breast lift

|

| Sexuality |

Sexuality increased significantly, in addition to the

improvement in sexual satisfaction, showing no significant

difference between patients who were or were not in a stable

relationship.

|

| Self-esteem |

The improvement in self-esteem appears

to be directly related to the patient's age, and the younger she

is, the greater the result in her emotional function.

|

| Psychosocial well-being |

Patients are more self-confident, more accepting of their own

bodies, strengthened in social environments and emotionally

healthy.

|

| Physical well-being |

Few or almost no complaints of

unbearable pain in the area of the breasts after surgery were

observed, with only the increased sensitivity in the area

standing out.

|

Chart 3 - Main factors observed in the change in the quality of life after

breast reconstruction after analyzing the articles by Monteiro et al.

(2015)x, Furlan et al. (2013)4, Ng et al. (2016)12 and Zhong et al.

(2013)13.

A study carried out with 47 patients resulted in a great improvement in the

sexuality of women undergoing mammoplasty surgery, showing an improvement in

sexual satisfaction and arousal25. In addition to this, other studies have shown that there

is a great benefit in performing breast reconstruction for post-mastectomized

patients, reporting that patients who have not undergone this procedure have

greater emotional fragility4.

Faced with so many negative impacts on the lives of women undergoing treatment

for breast cancer, there is still certain negligence on the part of

professionals about feminine emotionality, which is unacceptable since body and

mind are in common26.

Therefore, health professionals must support these patients, clarifying possible

doubts, providing emotional support and managing the case in the best possible

way to have the least likely impact on the woman’s life27.

Based on the review of the articles, it is possible to observe the importance of

aesthetic procedures in the physical and psychological recovery of women who

underwent a procedure as aggressive as mastectomy10. Surgical intervention through mastectomy can

be performed with conservative methods such as quadrantectomy and nodulectomy or

more radical methods that consist of total ablation of the breast and muscles.

It is known that the emotionality of these women undergoing these procedures is

affected throughout the treatment stage. However, it is mainly at the end of the

treatment that difficulties in adaptation, restrictions and even negative

repercussions in their sexual life arise20.

The complications of cosmetic surgery for breast repair and reconstruction are

difficult to resolve, as they are inherent in any medical procedure, whether it

is of low or high complexity. However, the surgeon must pay attention to risk

factors such as obesity and smoking, as these contribute to complications and

are essential to carry out a good preoperative period and strict follow-up after

surgery28. The risk of

performing this cosmetic surgery, being minimal, is offset by so many benefits

provided to women, the main ones being an improvement in self-esteem and a

feeling of greater femininity29.

Concerning the cost of surgery problems and others mentioned above, such as

possible complications, it is difficult to propose solutions to establish a more

beneficial scenario for both the system and the individual. A possible solution

would be to improve the active screening of the target population since, in the

early diagnosis, the number of procedures, mortality, and the cost of operations

decreases significantly compared to the spontaneous search for

patients11.

Thus, the right that women won, in 1999, to perform the procedure through the

SUS, associated with the fact that this procedure is performed soon after the

mastectomy, were important milestones in the fight for a better quality of life

for women victims of breast cancer11. Despite this achievement, it was only in 2018 that it was

possible to win the right to carry out bilateral repairs to maintain the

symmetry of the breasts through an update to the 1999 law, ensuring a better

aesthetic result and with good impacts on their quality of life11,30.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed that performing plastic surgery in women with

mastectomies greatly impacts several psychological, sexual, affective, and

social pillars of their lives. Despite having won several rights that address

mastectomy and its consequences, there are still adversities that could be

overcome with greater investment in secondary prevention, with more effective

active screening.

This measure would be important to reduce treatment costs since the early stages

of cancer require fewer interventions and less costly and less invasive

procedures.

As for the psychological impacts of the consequences of the surgery and

treatment, the preparation of professionals is essential to answer this

patient’s doubts and welcome her concerns and concerns. Therefore, the

naturalization of the suffering of these patients cannot occur, as it often

leads to negligence in care. And, an important part of this care, humanization

and dignification of women already takes place in the reconstruction surgery,

which aims to return a physical symbol of female sensuality and pride.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Cancer Observatory (GCO).

Estimated age-standardized mortality rates (world) in 2018, worldwide, female,

all ages [Internet]. Lyon: Cancer Today/WHO; 2018; [acesso em 2020 Nov 29].

Disponível em: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-multi-bars?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=countries&population=900&populations=900&key=asr&sex=0&

2. Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA). Mortalidade proporcional

não ajustada por todas as neoplasias, mulheres, Brasil, entre 2014 e 2018

[Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2018; [acesso em 2020 Nov 29].

Disponível em: https://mortalidade.inca.gov.br/MortalidadeWeb/pages/Modelo01/consultar.xhtml#panelResultado

3. Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA). Estimativa 2020:

incidência de câncer no Brasil [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: INCA;

2020; [acesso em 2020 Nov 29]. Disponível em: https://www.inca.gov.br/publicacoes/livros/estimativa-2020-incidencia-de-cancer-no-brasil

4. Furlan VLA, Neto MS, Abla LEF, Oliveira CJR, Lima AC, Ruiz BFO, et

al. Qualidade de vida e autoestima de pacientes mastectomizadas submetidas ou

não a reconstrução de mama. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013

Jun;28(2): 264-9.

5. Correio Brasiliense (BR). Demora no diagnóstico de

câncer leva à mastectomia em 70% dos casos [Internet].

Brasília (DF): Correio Brasiliense; 2018; [acesso em 2020 Nov 29].

Disponível em: https://www.correiobraziliense.com.br/app/noticia/ciencia-e-saude/2018/05/06/interna_ciencia_saude,678759/demora-no-diagnostico-de-cancer-leva-a-mastectomia-em-70-dos-casos.shtml

6. Lei no 11.664, de 29 de abril de 2008 (BR). Dispõe

sobre a efetivação de ações de saúde que

assegurem a prevenção, a detecção, o tratamento e o

seguimento dos cânceres do colo uterino e de mama, no âmbito do

Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS. Diário Oficial da

União, Brasília (DF), 29 abr 2008; Seção 1:

1.

7. Federação Brasileira de Instituições

Filantrópicas de Apoio à Saúde da Mama (FEMAMA). O

câncer de mama em números [Internet]. Porto Alegre: FEMAMA; 2019;

[acesso em 2020 Nov 29]. Disponível em: https://www.femama.org.br/site/br/noticia/o-cancer-de-mama-em-numeros

8. Lei no 12.802, de 24 de abril de 2013 (BR). Altera a Lei

nº 9.797, de 6 de maio de 1999, que “dispõe sobre a

obrigatoriedade da cirurgia plástica reparadora da mama pela rede de

unidades integrantes do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS nos casos de

mutilação decorrentes de tratamento de câncer”, para

dispor sobre o momento da reconstrução mamária.

Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF), 24 abr

2013.

9. Braga AKG, Santos TLC, Magalhães MAV. Processo de

reconstrução mamária em mulheres mastectomizadas. Rev

Interd. 2016;9(1):216-23.

10. Cammarota MC, Campos AC, Faria CADC, Santos GC, Barcelos LDP, Dias

RCS, et al. Qualidade de vida e resultado estético após

mastectomia e reconstrução mamária. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2019;34(1):45-57.

11. Mollinar ABP, Pereira IPC, Araújo JSF, Smith JSR, Guerra MCA,

Real Junior MMF, et al. Cirurgia oncoplástica e reconstrutiva da mama:

análise acerca dos direitos do paciente no âmbito do SUS. Braz J

Develop. 2020;6(8):54485-503.

12. Leal VCLV, Catrib AMF, Amorim RF, Montagner MA . O corpo, a cirurgia

estética e a Saúde Coletiva: um estudo de caso. Ciência

& Saúde Coletiva. 2010; 15 (1): 77-86.

13. Moura FMJSP, Silva MG, Oliveira SC, Moura LJSP. Os sentimentos das

mulheres pós-mastectomizadas. Esc Anna Nery. 2010; 14(3):

477-84.

14. Cesnik VM, Santos MA. Mastectomia e sexualidade: uma revisão

integrativa. Psicologia: Reflexões e Crítica. 2012; 25(2):

339-49.

15. Majewski JM, Lopes ADF, Davoglio T, Leite JCDC. Qualidade de vida em

mulheres submetidas à mastectomia comparada com aquelas que se submeteram

à cirurgia conservadora: uma revisão de literatura. Ciência

& Saúde Coletiva. 2012; 17(3): 707-16.

16. Cosac OM, Filho JPPC, Barros APGSH, Borgatto MS, Esteves BP, Curado

DMC, et al. Reconstruções mamárias: estudo retrospectivo de

10 anos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(1):59-64.

17. Colombo FG. Avaliação do grau de

satisfação de pacientes submetidas a reconstrução

mamária. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2013; 28(3): 355-60.

18. Gomes NS, Silva SR. Avaliação da autoestima de

mulheres submetidas à cirurgia oncológica mamária. Texto

Contexto Enferm. 2013; 22(2): 509-16.

19. Guimarães PAMP, Neto MS, Abla LEF, Veiga DF, Lage FC,

Ferreira LM. Sexualidade após mamoplastia de aumento. Rev Bras Cir Plast.

2015; 30(4): 552-559.

20. Guedes TSR. Imagem Corporal de Mulheres Submetidas Ao Tratamento Do

Câncer De Mama. Natal. Tese [Mestrado em Saúde Coletiva] -

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte; 2016

21. Alves VL, Sabino Neto M, Abla LEF, Oliveira CJR, Ferreira LM.

Avaliação precoce da qualidade de vida e autoestima de pacientes

mastectomizadas submetidas ou não à reconstrução

mamária. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica.

2017;32(2):208-17

22. Martins TNDO, Santos LFD, Petter GDN, Ethur JNDS, Braz MM, Pivetta

HMF. Reconstrução mamária imediata versus não

reconstrução pós-mastectomia: estudo sobre qualidade de

vida, dor e funcionalidade. Fisioter. Pesqui. 2017; 24(4):

412-19.

23. Villar RR, Fernandez SP, Garea CC, Pillado MTS, Barreiro VB, Martin

CG. Qualidade de vida e ansiedade em mulheres com câncer de mama antes e

depois do tratamento. Rev Latino-Am Emfermagem. 2017; 25:

e2958.

24. Casassola GM, Stallbaum JH, Pivetta HMF. Satisfação

com cirurgia oncológica da mama: Comparação entre pacientes

mastectomizadas com e sem reconstrução mamária. SIEPE

[Internet]. 14º de fevereiro de 2020 [citado 20º de novembro de

2020];10(3). Disponível em: https://periodicos.unipampa.edu.br/index.php/SIEPE/article/view/87256

25. Archangelo SDCV, Neto MS, Veiga DF, Garcia EB, Ferreira LM.

Sexuality, depression and body image after breast reconstruction. Clinics. 2019;

74:e883.

26. Cosac OM, Campos AC, Dias RCS, Costa RSC, Da-Silva SV, Damasio AA,

et al. Reconstrução mamária: estudo retrospectivo de 16

anos. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2019; 34(2): 210-7.

27. Volkmer C, Santos EKA, Erdmann AL Sperandio FR, Backes MTS,

Honório GTS. Reconstrução mamária sob a ótica

de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia: uma metaetnografia. Texto &

Contexto Enfermagem. 2019; 28: e20160442.

28. Carneiro MSF, Pinheiro CPO, Feitosa FVV, Soares MN, Rabelo IV, Lebre

P, et al. Repercussões psicológicas da cirurgia plástica em

mulheres mastectomizadas. Braz J of Develop. 2020; 6(7):

47743-51.

29. Ng SK, Hare RM, Kuang RJ, Smith KM, Brown BJ, Hunter-Smith DJ.

Breast Reconstruction Post Mastectomy: Patient Satisfaction and Decision Making.

Ann Plast Surg. 2016; 76(6): 640-4.

30. Zhong T, Temple-Oberle C, Hofer S, Beber B, Semple J, Brown M, et

al.; MCCAT Study Group. The Multi Centre Canadian Acellular Dermal Matrix Trial

(MCCAT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial in implant-based

breast reconstruction. Trials 2013, 14: 356.

31. Brasil. Lei n. 9.797, de 06 de maio de 1999. Dispõe sobre a

obrigatoriedade da cirurgia plástica reparadora da mama pela rede de

unidades integrantes do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS nos casos de

mutilação decorrentes de tratamento de câncer.

Diário Oficial da União. 06 mai 1999.

32. Brasil. Lei n. 13.770, de 19 de dezembro de 2018. Altera as Leis n

º 9.656, de 3 de junho de 1998, e 9.797, de 6 de maio de 1999, para

dispor sobre a cirurgia plástica reconstrutiva da mama em casos de

mutilação decorrente de tratamento de câncer. Diário

Oficial da União. 19 dez 2018.

33. Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA). Câncer de mama:

vamos falar sobre isso?[site]. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2019 [acesso em 29 nov

2020]. Disponível em: https://www.inca.gov.br/campanhas/outubro-rosa/2015/cancer-de-mama-vamos-falar-sobre-isso

34. Crippa CG, Hallal ALC, Dellagiustina AR, Traebert EE, Gondin G,

Pereira C. Perfil clínico e epidemiológico do câncer de

mama em mulheres jovens. Arquivos Catarinenses de Medicina. 2003; 32(3):

50-8.

35. Santos LS, Diniz, GRS. Saúde mental de mulheres donas de

casa: um olhar feminista-fenomenológico-existencial. Psicologia

Clínica, 2018, 30(1): 37-59.

36. Correia KML, Borloti E. Mulher e Depressão: Uma

Análise Comportamental-Contextual. Acta comport., 2011; 19(3):

359-73.

37. Oliveira JO, Peruch MH, Gonçalves S, Haas P. Padrão

hormonal feminino: menopausa e terapia de reposição. Revista

Brasileira de Análises Clínicas, 2016; 48(3):

198-210.

38. Brasil. Parecer técnico Nº 23/GEAS/GGRAS/DIPRO/2018.

Cobertura: procedimentos diversos - mama e sistema linfático

(mastectomia/ mastoplastia). Agência Nacional de Saúde

Suplementar. 2018.

1. Dynamic College of Vale Do Piranga, Ponte Nova,

MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Lúcia Meirelles

Lobão, Rua G, nº 205, Paraíso, Ponte Nova, MG,

Brasil, Zip Code 35430-302, E-mail:

lucia.fadip@gmail.com

Article received: April 09, 2021.

Article accepted: July 14, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Institution: Dynamic Faculty of Vale do Piranga, Ponte Nova, MG, Brazil.