Case Reports - Year 2012 - Volume 27 -

Abdominal wall reconstruction with alloplastic mesh after Mycobacterium infection

Reconstrução de parede abdominal com tela aloplástica após infecção por micobactéria

ABSTRACT

The present report is a case study of a 51-year-old woman who underwent hysterectomy by videolaparoscopy, and eventually developed a mycobacterial infection. Treatment comprised antimicrobial administration, surgical debridement, and reconstruction of the abdominal wall with a synthetic mesh. During the postoperative period, the herniation of the abdominal wall required substitution of the mesh and subsequent abdominoplasty. This case report indicates the importance of preventing mycobacterium infection and provides treatment guidelines to optimize functional and aesthetic results.

Keywords: Mycobacterium. Abdominal wall/surgery. Surgical mesh.

RESUMO

Os autores relatam o caso de paciente do sexo feminino, com 51 anos de idade, submetida a histerectomia por videolaparoscopia, com evolução para quadro de infecção por micobactéria. Realizado tratamento com associação de antimicrobianos, debridamento cirúrgico e reconstrução de parede abdominal com tela sintética. Na evolução pós-operatória, a paciente apresentou herniação de parede abdominal, corrigida com a substituição por nova tela aloplástica e abdominoplastia. O relato do caso alerta para a importância dos cuidados na prevenção da infecção por micobactéria e do adequado tratamento para otimização funcional e estética.

Palavras-chave: Mycobacterium. Parede abdominal/cirurgia. Telas cirúrgicas.

Abdominal wall reconstruction can be performed in several levels of complexity to correct a variety of defects from discreet tissue loss to important defects in the total tissue thickness, with visceral involvement1. Among the common causes of abdominal injury, the most relevant include incisional hernia, neoplasia, infection, irradiation, and trauma.

Postoperative infections by atypical mycobacterium have been reported across the different medical specialties, including plastic surgery. Such infections are observed after procedures such as liposuction and augmentation mammoplasty, and most often after video laparoscopic abdominal surgery2.

In addition to the local control of the infection, it is critical to restore the integrity of the abdominal wall to optimize the aesthetic results. This can be achieved with the aid of a synthetic mesh combined with abdominoplasty, which provides suitable coverage of the visceral organs in cases showing extensive musculofascial defects3. The available mesh materials include polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, Gore-Tex), PTFE multifilament (Teflon), multifilament (Surgipro), polypropylene monofilament (Marlex), compound polypropylene monofilament (Proceed), double polypropylene filament (Prolene), and polyester multifilament (Mersilene).

The ideal synthetic mesh must possess the following characteristics: it must be chemically inert, it should remain unaffected by tissue fluids, it should not trigger foreign body responses, and it should not be carcinogenic or allergenic. In addition, it should be able to withstand mechanical stresses and be sterilized. The thread used for the fixation of the mesh must be inert, non-absorbable, and a monofilament1.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old woman of mixed racial background, presenting with hypertension and without diabetes mellitus or a history of smoking, underwent hysterectomy by video laparoscopy on November 13, 2006. The patient developed transvaginal hemorrhage 16 days postoperatively, which required a new surgical approach and hospitalization in an Intensive Therapy Center for 3 days. Seven days after the second intervention, the patient exhibited serobloody secretion from the surgical wound, followed by wound dehiscence at the trocar sites with associated hyperthermia and arthralgia.

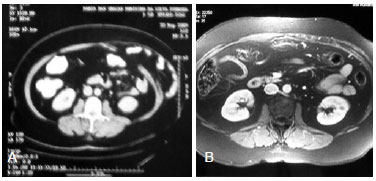

Computerized tomography of the entire abdomen showed the presence of heterogeneous supravesicular nodes, measuring approximately 1.3 × 1.3 cm, attached to the anterior abdominal wall.

On January 15, 2007, we removed a large granuloma of the abdominal wall that extended into the peritoneal cavity, requiring its reconstruction using Marlex mesh. A sample of the tissue removed was subjected to bacteriological analysis, and indicated infection by Mycobacterium fortuitum. As this was already suspected, and treatment with ethambutol, claritromycin, and terizidone had already been initiated, it was continued for 3 months, after which minocycline was added and the complete drug regimen was maintained for an additional 3 months. The patient developed herniation of the abdominal wall, which was corrected using a synthetic mesh on July 28, 2008.

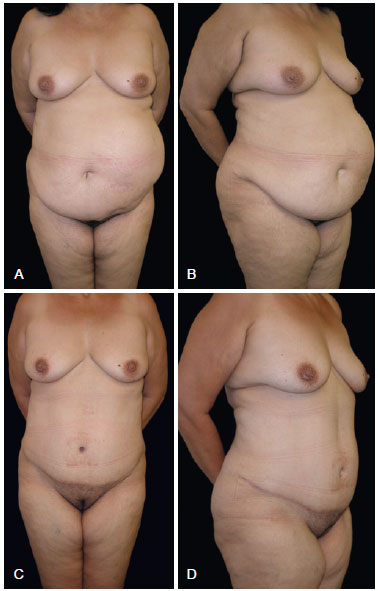

Although the infectious process was effectively controlled, the herniation of the abdominal wall persisted, resulting in a deformity in the abdominal wall as well as discomfort during moderate physical effort. In August 2009, the second alloplastic mesh was exchanged for a Proceed mesh with conventional abdominoplasty (Figures 1 to 4).

Figure 1 - In A and B, preoperative appearance. In C and D, postoperative appearance after 147 days.

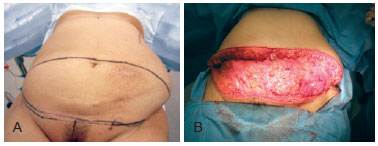

Figure 2 - In A, surgical marking of the abdominoplasty. In B, resection of excessive skin and adipose tissue of the lower abdomen, with a piece weighting 1.935 g.

Figure 3 - In A, defect in the abdominal wall. In B, positioning of the polypropylene monofilament mesh interposed by PDS in relation to the deepest layer of regenerated oxidated cellulose (Proceed), which can be in direct contact with the abdominal viscera. In C, points of fixation of the mesh with monofilament thread. In D, final appearance of the abdominal wall. PDS = polydioxanone suture.

Figure 4 - In A, computerized tomography images showing the defect of the abdominal wall on the left side, despite the use of a polypropylene monofilament mesh. In B, Nuclear magnetic resonance obtained 7 months after applying the polypropylene monofilament mesh composed of regenerated cellulose during an abdominoplasty procedure.

The patient evolved asymptomatically, without functional limitations, and was able to perform her routine activities. The patient was satisfied with the final aesthetic result.

DISCUSSION

Although mycobacterial infections can be diagnosed from samples of draining fluid, the analysis of tissue samples obtained from the infected area provides greater accuracy. A wound swab is simple, but it is not very useful. The initial identification of the bacteria may be achieved by staining for acid-alcohol resistant bacilli (BAAR) following the method described by Ziehl-Neelsen. Cultures are usually grown in thioglycolate, blood agar, chocolate agar, or MacConkey and Lowenstein-Jensen media, which is specific for the growth of mycobacterium. The growth of microorganisms in these media may take several weeks, and the culture must be kept under observation for up to 8 weeks. The histopathological findings associated with mycobacterial lesions include chronic granulomatous inflammation and necrotic granulomas, with epithelioid cells, histiocytes, and giant cells2.

There are no specific standards for the treatment of mycobacterial infections. In general, disease control is based on antibiograms. A serious infection may be treated initially with a first or second generation cephalosporin combined with aminoglycosides administered intravenously (for instance, cephalothin and amikacin). The use of carbapenems or quinolones is another treatment option. In cases of acceptable evolution of the clinical picture after 2-4 weeks of treatment, the medication is administered orally.

Most cases show infections of light or moderate intensity, which are treated by oral administration of claritromycin combined with 1 or 2 antimicrobial agents such as ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, or tetracycline.

Although there are no established guidelines for the duration of treatment, a minimum of 3 months of antimicrobial therapy is recommended depending on the clinical manifestations, clinical evolution, and immunological status of the patient4,5.

Whenever indicated, draining, surgical debridement, or removal of the prosthesis at the surgical site should be performed, as it is a favorable environment for mycobacterial survival. Alloplastic meshes with pores smaller than 10 microns must be removed when an infection is present because they do not allow for appropriate interpenetration of the tissues. On the other hand, meshes with pores larger than 75 microns such as the Proceed mesh, which is a monofilament that shows adequate tissue incorporation and is associated with reduced risk of infection, do not need to be removed6,7. In addition, the Proceed mesh can be applied directly to the abdominal viscera because it contains an inner layer of oxidated regenerated cellulose1.

CONCLUSIONS

The effective control of mycobacterial infections requires a comprehensive preventive approach consisting of rigorous sterilization of all surgical instruments and materials including optical fiber, methylene blue, and silicone implants8-10.

The early diagnosis of mycobacterial infections and an effective treatment regimen, including antibiotic therapy and surgical debridement, are critical to ensure the positive evolution of the patient. Moreover, several synthetic materials and surgical repair techniques in plastic and reconstructive surgery are currently available for the proper reconstruction of the abdominal wall.

REFERENCES

1. Alves JCRR, Silva Filho AF, Pereira NA, Ferrer KS, Carvalho EES. Reconstrução da parede abdominal. In: Mélega JM, Montoro AF, Albertoni WM, eds. Cirurgia plástica: fundamentos e arte. Cirurgia reparadora de tronco e membros. Rio de Janeiro: Medsi; 2004. p. 242-56.

2. Macedo JLS, Maierovitch C, Henriques P. Infecções pós-operatórias por micobactérias de crescimento rápido no Brasil. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(4):544-51.

3. Hsu PW, Salgado CJ, Kent K, Finnegan M, Pello M, Simons R, et al. Evaluation of porcine dermal collagen (Permacol) used in abdominal wall reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(11):1484-9.

4. Nagao M, Sonobe M, Bando T, Saito T, Shirano M, Matsushima A, et al. Surgical site infection due to Mycobacterium peregrinum: a case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(2):209-11.

5. Régnier S, Martinez V, Veziris N, Bonvallot T, Meningaud JP, Caumes E. Traitment des infections cutanées à Mycobacterium fortuitum: deux cas. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135(8-9):591-5.

6. Rosenberg J, Burcharth J. Feasibility and outcome after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair using Proceed mesh. Hernia. 2008;12(5):453-6.

7. Berrevoet F, Fierens K, De Gols J, Navez B, Van Bastelaere W, Meir E, et al. Multicentric observational cohort study evaluating a composite mesh with incorporated oxidized regenerated cellulose in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2009;13(1):23-7.

8. Brickman M, Parsa AA, Parsa FD. Mycobacterium cheloneae infection after breast augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;29(2):116-8.

10. Angeli K, Lacour JP, Mantoux F, Roujeau JC, André P, Truffot-Pernot C, et al. Infection cutanée à Mycobacterium fortuitum après lifting. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131(2):198-200.

11. Haiavy J, Tobin H. Mycobacterium fortuitum infection in prosthetic breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(6):2124-8.

1. Full member of the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery) - SBCP, member of the Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões (Brazilian College of Surgeons), member of the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS), Chief of the Service of Plastic Surgery of the Hospital Federal do Andaraí (Plastic Surgery Service of the Federal Hospital of Andaraí), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

2. Associate member of SBCP, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

3. Associate member of SBCP, plastic surgeon of the Service of Plastic Surgery of the Hospital Federal do Andaraí (Plastic Surgery Service of the Federal Hospital of Andaraí), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

Correspondence to:

Thyago Menezes de Carvalho

Av. Álvaro Otacílio, 3535 - apt. 402 - Ponta Verde

Maceió, AL, Brazil - CEP: 57035-180

E-mail: tmcarvalho@gmail.com

Article submitted to SGP (Sistema de Gestão de Publicações/ Manager Publications System) of RBCP (Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica/Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery).

Article received: April 14, 2010

Article accepted: July 26, 2010

Study conducted at the Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica do Hospital Federal do Andaraí (Plastic Surgery Department of the Federal Hospital of Andaraí), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter