Case Report - Year 2014 - Volume 29 -

Surgical treatment of primary pachydermoperiostosis: report of two cases

Tratamento cirúrgico da paquidermoperiostose primária - relato de dois casos

ABSTRACT

Primary pachydermoperiostosis is a rare disease characterized by excessive skull affixing of the periosteum, coexisting with thickening of the epidermis and dermis (pachydermia), thereby causing gross deformities. Owing to the variety of affected structures, there are several surgical options and complementary methods that are used in the treatment of facial alterations in these patients. This report describes the use of subperiosteal detachment as an aesthetic treatment option for the faces of two patients with primary pachydermoperiostosis, operated at the Hospital das Clínicas of the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Keywords: Primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy; Surgery; Rhytidectomy.

RESUMO

A paquidermoperiostose primária é uma doença rara, caracterizada por aposição excessiva do periósteo do crânio, coexistindo com espessamento da epiderme e derme (paquidermia), provocando deformidades grosseiras. Devido à diversidade de estruturas acometidas, há várias opções cirúrgicas e métodos complementares que são utilizados no tratamento das alterações faciais desses pacientes. Esse trabalho apresenta o lifting subperiosteal como uma opção de tratamento estético para a face de pacientes portadores dessa síndrome, através do relato de dois casos operados no Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

Palavras-chave: Osteoartropatia Hipertrófica Primária; Cirurgia; Ritidoplastia.

Pachydermoperiostosis, also known as Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome or primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA), is a rare disease characterized by excessive skull affixing of the periosteum, coexisting with thickening of the epidermis and dermis (pachydermia), thereby causing gross deformities. It has an autosomal dominant inheritance with variable expression. This rare disease begins insidiously and is more common in men than in women1.

The onset of the condition is typically in adolescence, when skin and bone changes become progressive and severe for 5-20 years and do not change for the rest of life2.

Some authors consider the main manifestations of primary HOA as increased volume of the extremities, Hippocratic fingers, nails "on watch glass," pachydermia, and neuromuscular or joint complaints. However, in recent years, similar frameworks have been described as secondary HOA to lung disease with suppurative characteristics and infiltrative or malignant or benign intrathoracic tumors that exhibit the same clinical signs marked as pathognomonic of primary HOA. For these reasons, it is not possible to distinguish the two forms unless the clinical course occurs or primitive pulmonary lesions are not present. However, secondary HOA has a later onset, shows no family or hereditary occurrence, and features more acute and painful bone alterations3.

Radiographic findings differ between these conditions. In primary HOA, the periosteal reaction is irregular and poorly defined, contrary to the linear deposit seen in secondary HOA. The diagnosis of primary HOA is accomplished primarily by radiological findings and clinical features consisting of proliferation periosteal with new symmetrical and bilateral bone formation (in thin layers becoming progressively irregular, rough, and rolling) in the long bones that is more evident in the insets of the tendons and ligaments. The medullary spaces appear normal. Therefore, the diagnosis of primary HOA should be considered after the exclusion of secondary HOA in any teen presenting with arthralgia, "clubbing" fingers, and family history in whom the characteristics of HOA are confirmed by radiographic findings3.

Clinical manifestations include skeletal abnormalities, thickening of the skin on the face and scalp, and deep nasolabial folds and frowning on the forehead and scalp that lend a leonine appearance. The vertical and horizontal dimensions of the upper eyelids are increased, causing varying degrees of ptosis. The skin is oily, with excessive sweating, mainly in the palms of the hands and soles of the feet4.

Owing to the variety of affected structures, it is not surprising that there are several surgical options and complementary treatments to minimize the changes caused by the disease. Among these, we highlight conventional techniques of facial rejuvenation, direct resection of the grooves and skin excess, fillers with hyaluronic acid, and various techniques for the treatment of ptosis.

The clinical treatment of this disease includes isotretinoin, retinoids, and colchicine5,6,7 and is inefficient. However, the clinical course of the disease is self-limited; in most cases, plastic surgery is intended solely for aesthetic improvement. The deformities caused by pachydermoperiostosis cause patients psychosocial inconvenience, which requires treatment.

This report presents a treatment option for the face and scalp of patients with this syndrome.

CASE REPORT

Here we present the surgical treatment of two patients with pachydermoperiostosis who underwent surgery between 2006 and 2009. In the cases discussed, the diagnosis of primary HOA was based on clinical changes without any pulmonary disease, family history, and characteristic radiographic findings.

The two male patients were 27 years and 30 years of age, respectively, and the main complaints were the wrinkles of the frontal region and noticeable face furrows. In addition to these manifestations, they had thickening of the fingers and finger clubbing without other comorbidities. One of them was an inveterate smoker, having started the habit after the onset of disease. Both had symptom onset during late adolescence, at 18 years of age.

The proposed treatment was facial rhytidectomy, which was to be performed in two stages. In the first stage, coronal incision with subperiosteal detachment, periosteal resection, and cauterization of the frontal muscle, which was thickened, was performed on the upper third of the face. The procerus muscles and corrugator were also treated, and the excess scalp was removed (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 (A) Treatment of the frontal region and resection of excess skin. (B) Detachment of the middle third of the subperiosteum using the Caldwell-Luck incision. (C) Detachment in the subcutaneous plane and fixation of the periosteum in the temporal fascia

Four months later, we proceeded to the second surgical stage, which consisted of rhytidectomy of the middle third of the face using preauricular incision extending from the upper pole of the ear to the outer corner of the eye. The detachment in the subcutaneous plane was extended by about 3 cm in the centripetal direction. The subperiosteal detachment of the maxilla and zygoma was carried out through an incision in the bilateral gingival superior sulcus (Caldwell-Luck incision; Figure 1B). Subsequently, the periosteum was attached to the temporal fascia, with suspension of the middle third of the face (Figure 1C), which was achieved with upper and lower blepharoplasty with resection of excess skin. The thickened periosteum was not resected.

Noteworthy of this technique is the transoperative bleeding, which necessitated the two-step approach, despite the use of infiltration with saline solution and adrenaline in a 1: 500,000 ratio.

In the postoperative stage of the first intervention, in the patient who smoked, necrosis was observed in the middle region of the glabellar flap, a triangular area with a superior base of about 5 cm, which healed with secondary intervention after serial debridement and dressing and did not affect the end result. In the postoperative stage of the second intervention, in the patient who smoked, there was a small region of necrosis in the right pre-auricular area, with good outcomes after conservative treatment. The non-smoker patient had no postoperative complications.

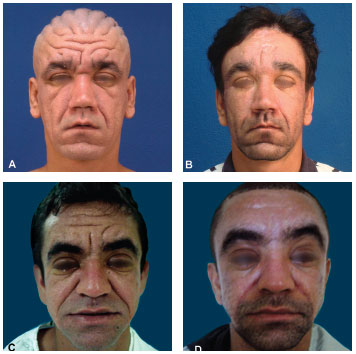

Both patients were satisfied with the results, indicating improvement in the wrinkles and leonine appearance of the face. Compared with the preoperative status (Figures 2A and 2C), we observed a marked improvement 8 months after the second surgery, with attenuation of the grooves, which were deep preoperatively (Figures 2B and 2D). The scalp was not treated in any of the patients, because these changes are camouflaged by the hair.

Figure 2 (A) and (B). Pre and postoperative (8 months) images of the first patient (C) and (D). Pre and postoperative (8 months) images of the second patient

DISCUSSION

Pachydermoperiostosis was first described by Touraine-Solente-Gole in 1935 as a characteristic syndrome. A classification was proposed in which the full form was characterized by pachydermia and digital and periostosis clubbing; the complete form featured pachydermia with minimal skeletal changes, and the incomplete form did not include pachydermia8. Family history is positive in 25-38% of patients.

Our patients had the typical signs of the complete form of the syndrome with thickened skin, deep grooves, clubbing, bone neoformation, and cortical thickening of the distal ends of the long bones. The patients' main complaints were related to facial alterations that gave them a leonine and aged appearance at an early age.

Surgical treatment with traditional procedures such as upper and lower blepharoplasty, skin zone resection, and conventional rhytidectomy are inefficient9,10. Rhytidectomy, with subperiosteal detachment of the upper and middle thirds of the face compared with conventional methods, was more effective in the treatment of deep wrinkles since it threatens its cause, the thickened periosteum11.

The necrosis presented in the patient who smoked had little effect in the end since scar retraction reduced the area extent, and the patient was satisfied with the results. We emphasize here the extent and depth of wrinkles efficiently treated with the method described herein (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION

We conclude that rhytidectomy, with subperiosteal detachment of the upper and middle thirds of the face in conjunction with resection of the thickened periosteum on the face and scalp associated with upper and lower blepharoplasty, is a safe and effective treatment for the anatomical changes caused by pachydermoperiostosis that boasts aesthetically satisfactory results.

REFERENCES

1. Castori M, Sinibaldi L, Mingarelli R, Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, Dallapiccola B. Pachydermoperiostosis: An update. Clin Genet. 2005;68(6):477-86.

2. Kerimovic-Morina DJ, Mladenovic V. Primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy in 32 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(suppl 7):51-6.

3. Carvalho TN, Araújo Jr CR, Fraguas Filho SR, Costa MAB, Teixeira KS, Ximemes CA. Osteoartropatia Hipertrófica Primária (Paquidemroperiostose): Relato de Dois Irmãos. Radiol Bras. 2004;37(2):147-9.

4. Latos-Bielenska A, Marik I, Kuklik M, Materna-Kiryluk A, Povysil C, Kozlowski K. Pachydermoperiostosis-critical analysis with report of five unusual cases. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1237-43.

5. Park YK, Kim HJ, Chung KY. Pachydermoperiostosis: trial with isotretinoine. Yonsei Med J. 1988;29:204-7.

6. Mattuci-Cerinic M, Ceruso M, Lotti T, Pignone A, Jajic I. The medical and surgical treatment of finger clubbing and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. A blind study with colchicines and a surgical approach to finger clubbing reduction. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(suppl 7):67-70.

7. Beauregard S. Cutis vertices gyrate and pachydermoperiostosis. Several cases in a same family. Initial results of the treatment of pachyderma with isotretinoin. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1994;121:134-7.

8. George L, Sachithandam K, Gupta A, Polimmod S. Frontal rhytidectomy as surgical treatment for pachydermoperiostosis: A case report. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19:61-3.

9. Seyhan T, Ozerdem OR, Aliagaoglu C. Severe complete pachydermoperiostosis (Touraine-Solente-Gole syndrome). Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11 Pt 1):1465-7.

10. Xu JJ, Li SK, Li YQ, Li Q, Wang YQ, Liu LQ. Treatment and pathologic change of pachydermoperiostosis. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2003;19:423-5.

11. Monteiro E, Carvalho P, Silva A, Ferraro A. Frontal rhytidectomy: a new approach to improve deep wrinkles in a case of pachydermoperiostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1189-90.

1 - Plastic Surgeon - Associate Member of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (BSPS)

2 - Plastic Surgeon - Full Member of the SBCP; Member of the Brazilian Association of Craniomaxillofacial Surgery; Assistant Professor, Department of UFMG School of Medicine Surgery

3 - Plastic Surgeon - Member of the SBCP; Adjunct Professor, Surgery Department of the Faculty of Medicine UFMG; Doctor of Medicine; Coordinator of the Plastic Surgery Service of the Clinical Hospital

4 - Plastic Surgeon - Associate Member of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (BSPS)

5 - Plastic Surgeon - Associate Member of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (BSPS)

6 - Plastic Surgeon - Associate Member of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (BSPS)

Corresponding Author:

Joyce de Sousa Fiorini Lima

Av. Alfredo Balena, 110 - 7º andar - Bairro Santa Efigênia

Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais - CEP 30130-100

Telefone: 31-9165-3801 Fax: 31-3409-9926

Article received: March 29, 2011

Article accepted: June 18, 2011

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter