Original Article - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

The use of virtual planning in orthognathic surgery

O uso do planejamento virtual na cirurgia ortognática

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Orthognathic surgery involves the manipulation of facial bone architecture through osteotomies to restore form and function, correcting malocclusion, maxillomandibular disproportions, and facial asymmetries. Virtual planning in orthognathic surgery is carried out with the help of software that uses real measurements of the craniofacial skeleton and records of the patient's occlusion through 3D analysis.

Method: 18 patients with dentofacial deformities were evaluated, according to Angle's classification, who underwent orthognathic surgery using virtual planning between 2018 and 2019. The inclusion criteria were patients between 16 and 60 years old with maxylo-mandibular disproportions in which orthodontic treatment alone was not sufficient. Exclusion criteria were the presence of cystic or tumoral lesions in the jaw and clinical comorbidities that contraindicated surgery. Virtual planning was carried out on all patients, using Dolphin® Imaging 11 software and surgical guides made with a 3D printer.

Results: The intermediate surgical guide presented perfect adaptation on the occlusal surfaces, promoting great stability for the repositioning and fixation of the maxilla in intermediate occlusion. The 18 operated patients responded as "completely satisfied" in relation to the aesthetic-functional result in this series studied. A very great similarity was found between the position of the maxillofacial skeleton in the preoperative virtual planning and that obtained post-operatively through the evaluation of teleradiography.

Conclusion: Virtual planning in craniomaxillofacial surgery has numerous advantages, such as reduced pre-operative laboratory time, greater precision in the creation of surgical guides, and better reproducibility of simulated results.

Keywords: Orthognathic surgery; Surgical navigation systems; Imaging, threedimensional; Planning techniques; Software; Maxillary osteotomy; Mandibular osteotomy; Craniofacial abnormalities; Cone-beam computed tomography.

RESUMO

Introdução: A cirurgia ortognática envolve manipulação da arquitetura óssea facial,

através de osteotomias, para restaurar a forma e a função, corrigindo a má

oclusão, as desproporções maxilomandibulares e assimetrias faciais. O

planejamento virtual em cirurgia ortognática é realizado com ajuda de

softwares que utilizam as medidas reais do esqueleto

craniofacial e registros da oclusão do paciente, através de uma análise

3D.

Método: Foram avaliados 18 pacientes com deformidades dentofaciais, de acordo com a

classificação de Angle submetidos a cirurgia ortognática com o uso do

planejamento virtual, entre 2018 e 2019. Os critérios de inclusão foram

pacientes entre 16 e 60 anos com desproporções maxilo-mandibulares nas quais

o tratamento ortodôntico isolado não era suficiente. Os critérios de

exclusão foram a presença de lesões císticas ou tumorais nos maxilares e

comorbidades clínicas que contraindicavam a cirurgia. O planejamento virtual

foi realizado em todos os pacientes, utilizando o software

Dolphin® Imaging 11 e os guias cirúrgicos confeccionados em

impressora 3D.

Resultados: O guia cirúrgico intermediário apresentou adaptação perfeita nas faces

oclusais promovendo grande estabilidade para o reposicionamento e fixação da

maxila na oclusão intermediária. Os 18 pacientes operados responderam como

"totalmente satisfeitos" em relação ao resultado estético-funcional nessa

série estudada. Foi encontrada uma semelhança muito grande da posição do

esqueleto maxilofacial no planejamento virtual pré-operatório e o obtido no

pós-operatório, através da avaliação das telerradiografias.

Conclusão: O planejamento virtual em cirurgia craniomaxilofacial possui inúmeras

vantagens, como diminuição do tempo laboratorial pré-operatório, maior

precisão na confecção dos guias cirúrgicos e melhor reprodutibilidade dos

resultados simulados.

Palavras-chave: Cirurgia ortognática; Sistemas de navegação cirúrgica; Imageamento tridimensional; Técnicas de planejamento; Software; Osteotomia maxilar; Osteotomia mandibular; Anormalidades craniofaciais; Tomografia computadorizada de feixe cônico

INTRODUCTION

Orthognathic surgery involves the manipulation of facial bone architecture through osteotomies to restore form and function, correcting malocclusion, maxillomandibular disproportions, and facial asymmetries1. The repositioning of the jaws takes place through the use of surgical guides made in the laboratory (pre-operative) phase during surgical planning.

Virtual planning in orthognathic surgery is carried out with the help of software that uses real measurements of the craniofacial skeleton and records of the patient’s occlusion, through a 3D analysis, different from the 2D evaluation of conventional planning. It is possible to virtually simulate surgical movements of the maxilla, mandible, and chin in all directions and create surgical guides for 3D printing on the computer. Among the advantages, when compared to the conventional method, are greater precision in the translation of the surgical plan intraoperatively, in the creation of guides and a shorter time in executing the planning2,3.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this work is to demonstrate the use of virtual planning in a series of 18 cases of patients with dentoskeletal deformities treated through orthognathic surgery.

METHOD

Eighteen patients with dentofacial deformities were evaluated, according to Angle’s classification (Class 1, 2, and 3), who underwent orthognathic surgery using virtual planning between 2018 and 2019 at Hospital Felício Rocho - Belo Horizonte-MG. The inclusion criteria were patients between 16 and 60 years old with maxillomandibular disproportions, with or without asymmetries, in whom orthodontic treatment alone was not sufficient to correct the malocclusion and improve facial aesthetics. Exclusion criteria were the presence of cystic or tumoral lesions in the jaws and clinical comorbidities that contraindicated the surgical procedure.

Virtual planning was carried out on all patients, using Dolphin® Imaging 11 software and surgical guides made with a 3D printer. In all cases, multislice face or cone beam computed tomography scans, intraoral scanning of the dental arches, and intraoral and extraoral photos were used to carry out the planning. The surgical guides were all made in resin using the same 3D printer. The same surgeon carried out the virtual planning and execution of the surgeries. The surgeries were performed under general anesthesia through nasotracheal intubation.

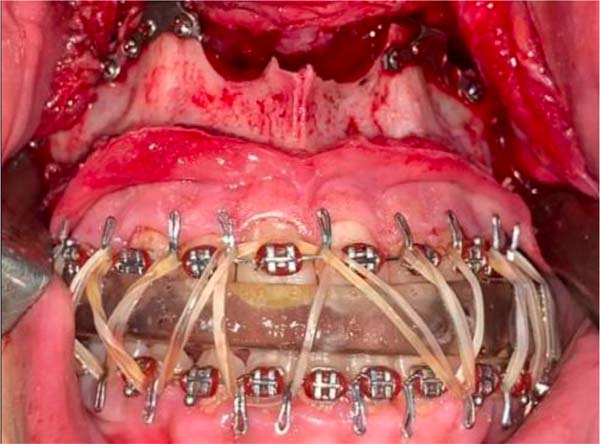

The surgical technique used in the maxilla was Lefort I osteotomy; in the mandible, sagittal osteotomies of the branches; and in genioplasty, basilar osteotomy. All surgeries started with the maxilla, which, after mobilization, was repositioned with the help of the intermediate guide created in virtual planning and fixed with osteosynthesis materials (plates and 1.5 screws) in the virtually planned position. Soon after, osteotomies of the mandible were performed, repositioned in class 1 occlusion, and fixed with 2.0 osteosynthesis material. A basilar osteotomy was performed to reposition the chin and fixed with a 2.0 Paulus plate.

The follow-up time was a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 14 months. The degree of satisfaction of the aesthetic-functional result with the use of virtual planning was evaluated using a numerical scale of 1-5 (1-completely dissatisfied, 2-dissatisfied, 3-neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4-satisfied, 5-completely satisfied ). Profile teleradiography was performed 7 days post-operatively to evaluate the maxillomandibular position.

RESULTS

The most common dentofacial anomaly was Class 2 (10 patients), followed by Class 3 (8 patients), with 3 patients in total presenting associated facial asymmetry. Females were prevalent (10 cases). Ages ranged from 16 to 55 years old. The time spent during virtual planning was 4 hours. Six patients underwent bimaxillary surgery (maxilla and mandible), 11 patients underwent trimaxillary surgery (maxilla, mandible, and chin), and 1 patient underwent monomaxillary surgery (mandible/chin) associated with arthroplasty of the left temporomandibular joint with a customized prosthesis.

The average hospitalization was 1 day. The average surgical time was 4 hours, without any serious local postoperative complications such as recurrence of malocclusion, pseudarthrosis, or infection in the 18 operated cases. A male patient developed rhabdomyolysis without renal repercussions, with no diagnosed etiology. The intermediate surgical guide presented perfect adaptation on the occlusal surfaces, promoting great stability for repositioning and fixing the maxilla in intermediate occlusion.

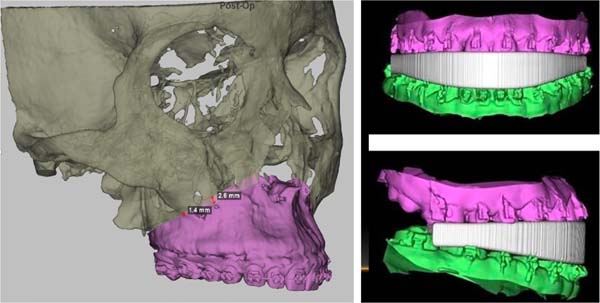

The 18 operated patients responded as “completely satisfied” in relation to the aesthetic-functional result in this series studied. A very great similarity was found between the position of the maxillofacial skeleton in the pre-operative virtual planning and that obtained post-operatively through the evaluation of cephalograms.

DISCUSSION

The historical development of orthognathic surgery dates back to 1906 when the first surgery to correct mandibular prognathism was performed on a medical student at the University of Washington by plastic surgery pioneer Vilray Blair. The father of orthognathic surgery, Hugo Obwegeser, a European surgeon with medical and dental training, introduced the technique of sagittal osteotomy of the mandibular rami in 1950 and was also the pioneer in performing bimaxillary surgery at the same surgical time. Bell, in 1975, in his work on the vascularization of the maxilla, guaranteed the safety of complete mobilization of Le Fort I osteotomies4.

In general, a pre-operative plan is the most important step in the workflow of orthognathic procedures3. Orthognathic surgery requires a precise assessment of complex dentofacial deformities of the craniofacial skeleton. It is indicated for the correction of maxillomandibular disproportions with aesthetic and/or functional repercussions (malocclusion, chewing, speech, or respiratory difficulties) in which isolated orthodontic treatment is not sufficient.

The success of the surgical plan depends not only on the accuracy of the skeletal and dental diagnosis of the deformity but also on the pre-surgical prediction of the proposed movements. It is the surgeon’s task first to define the original position of the dentofacial skeleton and then estimate the desired final position and, finally, develop a three-dimensional representation of the movements necessary to achieve the intended objective1.

Previously, conventional surgical planning used manual cephalometric analysis of lateral teleradiography, facial analysis, and sections of plaster models of the patient’s dental arches. The plaster models were then repositioned in the position determined by the surgeon, and surgical guides were manually created with acrylic resin in the new position of the jaws.

However, the traditional approach has its limitations, especially in the case of patients with major facial deformities or asymmetry, as 2D cephalometric images cannot provide complete information about 3D structures. When conventional 2D surgical plans are performed, unexpected problems may occur, such as a bone collision in the ramus area, pitch discrepancy, plane spin rotation, midline difference, and chin inadequacy5.

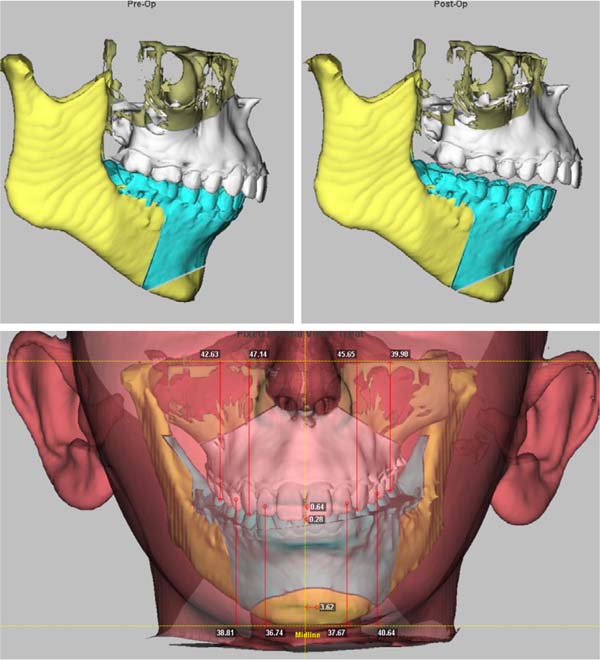

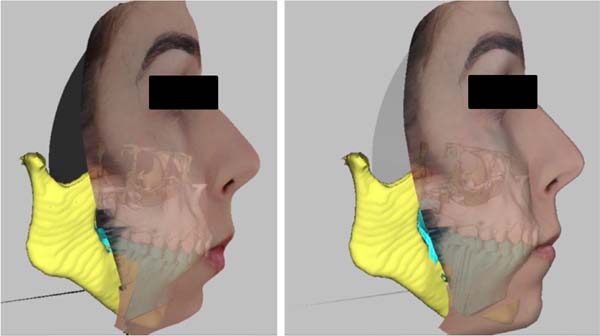

Advances in imaging methods such as cone beam tomography, multislice tomography with reliable reproduction of craniofacial anatomy, and manual scanners with a recording of dental occlusion in high definition have enabled the virtual execution of planning in orthognathic surgery, bringing a change in the treatment paradigm of dentoskeletal deformities. Virtual planning in orthognathic surgery is a process that integrates planning and surgical intervention through the use of software that performs cephalometric analysis in three dimensions (3D) of the anatomy of bone tissue, occlusion, and soft tissue (Figure 1).

The surgeon performs the virtual repositioning of the jaws (Figure 2) and creates surgical guides that will later be printed on a 3D printer and used during the procedure1,2,6 (Figures 3 and 4).

Currently, the technological advancement of 3D printing technology and the improvement of the elastic modulus of 3D printed surgical matrices have allowed increasingly precise results5.

Applications of virtual planning in craniomaxillofacial surgery include orthognathic surgery, TMJ prosthetic reconstruction, trauma, and oncologic reconstruction, to name a few.

In orthognathic surgery, specifically, the advantages are increased accuracy in the occlusal relationship, reduced surgery time, increased patient satisfaction, reduced cost7,8, and reduced planning time by up to 30%9. Furthermore, virtual planning allows for greater precision in predicting the positioning of soft tissues in the sagittal plane, and patients treated with it present greater symmetry in the frontal view3. Pre-operative surgery simulation allows measurements of up to one-hundredth of a millimeter, and when combined with 3D printed guides, the functional and aesthetic result is superior to traditional two-dimensional (2D) results. This reduced surgical time also directly translates into time under anesthesia and reduced total cost6.

In 2012, research using patient satisfaction through a subjective assessment of functional and aesthetic results showed that patients who underwent virtual planning reported more favorable scores than those who underwent traditional surgery7.

Virtual planning has challenged the current state of pre-operative preparation and procedures in orthognathic surgery. Associated with medical prototyping of 3D printing, it has become a significant tool, demonstrating to be highly accurate in terms of imaging, quantitative analysis, and predictability of planned surgical movements. Virtually created surgical guides are reliable in their construction and accuracy. Surgeons are reporting virtual surgery results with margins of error within 2mm of predicted maxillary and mandibular positions when comparing postoperative outcomes2,5 (Figure 5).

All these benefits can reduce planning time complications and surgical time compared to conventional planning1,2,4,8,10. The next generation of virtual planning will realize cutting guides for osteotomies and three-dimensional printed osteosynthesis plates, corresponding almost identically to the bone level in all planes of space8.

Future orthognathic surgical planning will undoubtedly be carried out by three-dimensional virtual planning. Financial expenses, treatment planning time, and intraoperative time will likely decrease due to the greater development of three-dimensional virtual planning techniques11.

CONCLUSION

Virtual planning in craniomaxillofacial surgery, especially in orthognathic surgery, is a tool that presents numerous advantages, such as reducing the time of the pre-operative laboratory phase, greater precision in the creation of surgical guides, and better reproducibility of simulated results.

REFERÊNCIAS

1. Hammoudeh JA, Howell LK, Boutros S, Scott MA, Urata MM. Current Status of Surgical Planning for Orthognathic Surgery: Traditional Methods versus 3D Surgical Planning. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(2):e307.

2. Farrell BB, Franco PB, Tucker MR. Virtual surgical planning in orthognathic surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2014;26(4):459-73.

3. Chen Z, Mo S, Fan X, You Y, Ye G, Zhou N. A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review Comparing the Effectiveness of Traditional and Virtual Surgical Planning for Orthognathic Surgery: Based on Randomized Clinical Trials. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79(2):471.e1-471.e19.

4. Chin SJ, Wilde F, Neuhaus M, Schramm A, Gellrich NC, Rana M. Accuracy of virtual surgical planning of orthognathic surgery with aid of CAD/CAM fabricated surgical splint-A novel 3D analyzing algorithm. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45(12):1962-70.

5. Alkhayer A, Piffkó J, Lippold C, Segatto E. Accuracy of virtual planning in orthognathic surgery: a systematic review. Head Face Med. 2020;16(1):34.

6. Jaisinghani S, Adams NS, Mann RJ, Polley JW, Girotto JA. Virtual Surgical Planning in Orthognathic Surgery. Eplasty. 2017;17:ic1.

7. Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF, Yuan P, Li J, Chen KC, et al. Algorithm for planning a double-jaw orthognathic surgery using a computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) protocol. Part 2: three-dimensional cephalometry. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(12):1441-50.

8. Steinbacher DM. Three-Dimensional Analysis and Surgical Planning in Craniomaxillofacial Surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(12 Suppl):S40-56.

9. Alkaabi S, Maningky M, Helder MN, Alsabri G. Virtual and traditional surgical planning in orthognathic surgery - systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;60(9):1184-91.

10. Wilson A, Gabrick K, Wu R, Madari S, Sawh-Martinez R, Steinbacher D. Conformity of the Actual to the Planned Result in Orthognathic Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(1):89e-97e.

11. Starch-Jensen T, Hernández-Alfaro F, Kesmez Ö, Gorgis R, Valls-Ontañón A. Accuracy of Orthognathic Surgical Planning using Three-dimensional Virtual Techniques compared with Conventional Two-dimensional Techniques: a Systematic Review. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2023;14(1):e1.

1. Hospital Felício Rocho, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil

2. Faculdade Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais,

Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

Corresponding author: Klaus Rodrigues Oliveira Rua Fernandes Tourinho, 840, Savassi, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, Zip Code: 30112-006, E-mail: contato@klausrodrigues.com.br

Article received: July 12, 2023.

Article accepted: August 20, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter